Pokémon Concierge and the Art of Generational Retention

Media Tribes is a home for my thoughts about building classic multi-generational franchises in the age of streaming, YouTube, Roblox, AI, and web3. It’s about the art of developing characters, stories, and worlds that bring people together despite the uncertainty of today’s increasingly fast-paced digital world.

This essay is about Pokémon Concierge, a show that embodies the art of generational fan retention. In the future I’ll alternate between deep dive essays about my favorite IP and nuts-and-bolts pieces about stuff we’re creating at CUDO.

If you like this piece, consider subscribing! Thanks for reading.

Great stories are like mirrors to our lives. We’re moved by relatable characters who navigate uncertainty, fight obstacles, and succeed in extraordinary circumstances because it gives us hope for our own.

Great storytellers have always understood this. But great story-driven franchises, those that appeal to legions of fans for many years, take it a step further.

They must touch the hearts of millions, not just once, but again and again for decades.

THE PROBLEM

Let’s say you create a hit TV show for elementary schoolers. What happens when your core audience grows up?

Do they outgrow your stories, or do your stories ‘grow up’ with them?

If your stories do grow up with them, will those same stories appeal to younger viewers who are now the age of your original core audience?

Or will you craft new stories for different ages? Where is there overlap and where is there separation? Will one group of fans ‘grow into’ another group of stories?

Most importantly, how can you speak to the same individual fan over decades as their own place in life changes?

MANY SOLUTIONS, MANY TRADE-OFFS

Look at the world’s most popular franchises and you’ll see many fixes to this problem, each with their own unique trade-offs.

Some, like PAW Patrol, remain fixed on one demographic at the cost of attrition. The franchise allows fans to ‘outgrow’ and exit the reach of the property as long as each fan is immediately replaced by at least one newcomer.

But this means the franchise must always reach more and more fans within the same age demographic in order to grow.

Others, like Star Wars, divide their fans into younger and older camps, make different content for each demo, and serve them along exclusive channels.

But this is complicated, expensive, and very few IPs are well-suited for content that exclusively serves fans of different ages.

A small handful like Bluey achieve the rare feat of double-coding their most poignant set pieces to mean one thing to a preschooler and another to a parent.

Not only is this approach beautiful, it is a recipe for superfandom as evidenced by the amount of adult Bluey evangelists online as Sleepytime climbs the ranks as one of the most written about and beloved episodes of television ever.

But not only is it an artistic accomplishment difficult to replicate, but it was an uphill battle for Bluey’s creator, Joe Brumm, who fought for years to convince industry gatekeepers of his vision. Innovative work this always goes against the grain.

And of course there’s the gold standard of multi-generational appeal, Pixar, who routinely craft movies which are wonderful the first time around and somehow become more and more meaningful each time you revisit them.

But aspiring to do things The Pixar Way is like telling a young tech company to be “like Apple.” It’s what everyone wants to do and very few succeed in doing.

SO WHICH IS THE BEST?

If you’re like me and you’re trying to optimize new IP, from the ground up, for cross-generational appeal (or if you’re managing preexisting IP and wish to break into a new age demographic) which is the best path forward?

Everyone’s answer will be different, but my favorite approach belongs to these guys:

Nintendo’s games have always been optimized for different ages (for example, the programing of Mario Kart to allow for first-time players to compete with experienced gamers without getting clobbered is amazing). And their approach to narrative is just as inventive, as evidenced by Nintendo's four-part series for Netflix, Pokémon Concierge, which practices a technique I call peripheral storytelling.

But before I dive into peripheral storytelling, here’s a rundown of this show.

AN ODD AND PEACEFUL SERIES

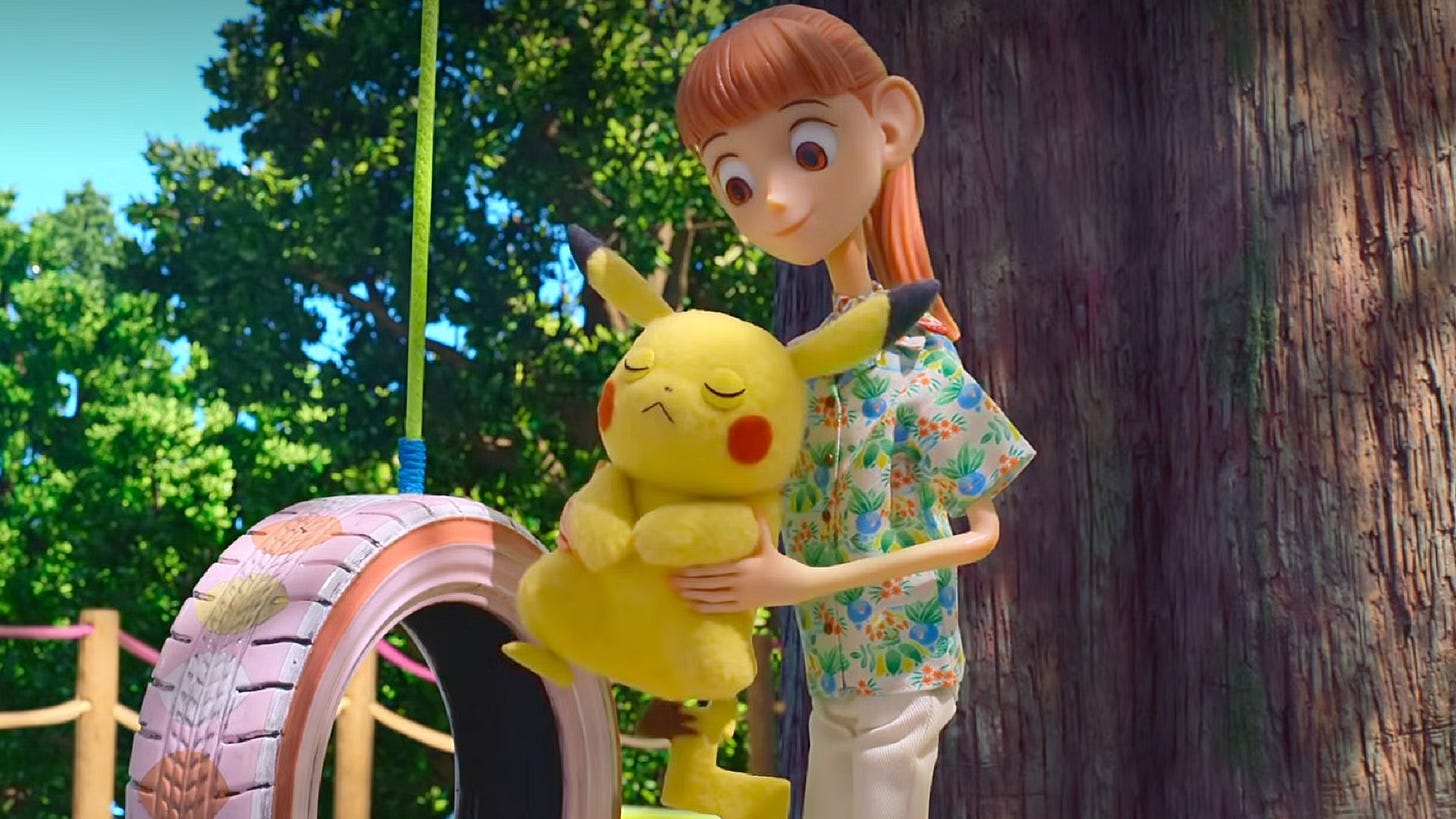

Pokémon Concierge follows Haru, an overworked young professional who leaves the big city to care for Pokémon at a peaceful resort.

Very little happens in terms of plot—the protagonist arrives, struggles to adjust to the slower pace of life at the facility, and in the process (re)learns how to relax, have fun, and care for the Pokemon guests. And that’s kind of it.

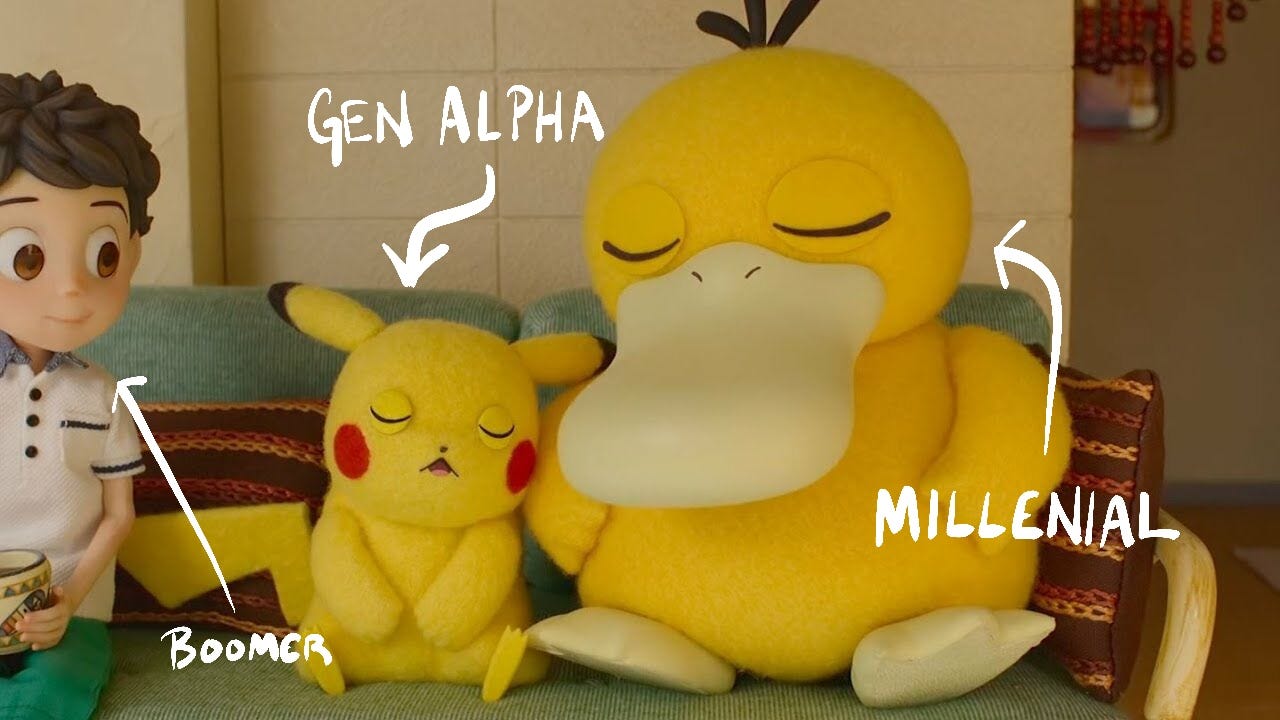

There are no gyms, no training, no fighting, and no violence. No beloved heroes and no familiar locations. Pikachu and Psyduck are featured heavily, but neither are characters from the original anime—they are new members of the same species.

These unconventional decisions help Concierge bring the world of Pokémon come alive more than anything else I’ve watched or played in the last twenty-five years.

My fondest memories of Red and Blue stand in the way my enjoyment of anything that’s come out since—from Saphire to Pokemon Indigo—because I know these canon entries won’t hold a candle to my own nostalgia for exploring Pallet Town when I was the age of Ash Ketchum.

Yet Concierge makes me feel as if Pokémon have been real this whole time.

The show’s approach is so delicate and tasteful that it leverages all my associations in this new series, inviting my imagination into the world beyond the frame, coloring the peripheries of the story. And this is what I mean by peripheral; stories set on the peripheries of a franchise instead of its dead center.

Pokémon Concierge does this on three levels: aesthetic, narrative, and contextual.

LEVEL 1 - AESTHETIC

Most obvious is Pokémon Concierge’s unique aesthetic. It’s the franchise’s first foray into stop-motion animation, gorgeously produced by Dwarf Studios.

Humans are made from vinyl and silicon while the pocket monsters themselves are felt, plastic, and paper.

These real-world elements give Pokemon a tactility unachievable by hand-drawn or computer-generated animation and make you feel like you can reach into the screen and pet them. Lighting falls on them in complex and beautiful ways.

These layers of aesthetic realism make them appear ‘real’ almost as if previous depictions were mere representations of each Pokémon and these puppets now represent the creatures as they exist in the world.

The Verge wrote about how the light bounces “off a Mudkip’s skin so effectively that it makes the show seem like it has captured their essences in a way that would never be possible in any other medium.” This is stop-motion’s novelty, and it’s paired with other playful elements of form.

There are hand-painted silhouettes used as introductions and interstitials to keep the busy urban world from which Haru arrives off-screen and therefore in the territory of our imaginations. There are unusual black and white transitions that feel more experimental than a franchise as massive and popular as Pokémon.

2. NARRATIVE

Instead of a traditional narrative structure, the series unfolds as a series of evocative moments and naturalistic routines.

It’s closer to an early Miyazaki movie than to any previous Pokémon series, and the fantasy at the heart of the story—slowing down when life gets stressful—has more in common with Stardew Valley than any Pokémon game.

Conflicts are so mild that you’d think Concierge was a pre-school show by their descriptions; a Psydyck has a headache. A Wingull steals an inner-tube. A Pikachu is shy. These aren’t just plot points, these are summaries of episodes. Yet Concierge doesn’t feel like a show for young children (although it could exist as one).

Taken together, these thoughtful breaks from convention stand in sharp contrast to any previous Pokémon series and, as a result make you feel as if you’re peeking into the world of Pokémon while nobody’s looking—these are the quiet moments between the franchise’s signature fights, tournaments, and epic quests.

3. CONTEXT

Finally, there’s the contextual ways Concierge defines its relationship with the Pokémon franchise as a whole.

None of the characters are canon, which makes Concierge seem more like a gently-paced example of Pokémon fan fiction than something by Nintendo.

Across the world of Concierge are little self-conscious elements of the world beyond the frame, like a Pokéball teapot, a household object shaped and hand-painted like a famous Pokémon, or a painting someone crafted of a Pikachu.

These objects invite you to wonder at the humans’ relationship to the creatures; to picture how these objects are designed, created, bought, and sold in peoples’ homes.

You can imagine hearing of the adventures of Ash and his friends from the quiet tropical island on which Concierge is set—making the stories of the franchise’s canon feel real, as they are relegated to the peripheries of our minds.

This approach appeals to me because it works thoughtfully alongside my nostalgia instead of trying to resurrect or replace it. Concierge isn’t competing with my memories, it’s using them to make the world of Pokémon feel richer.

WAIT, AREN’T WE JUST TALKING ABOUT SPIN-OFFS?

Don’t other examples like The Mandalorian, Fantastic Beasts, and Puss in Boots do variations of the same thing as Concierge?

There are some key differences between spin-offs and peripheral storytelling and using these popular examples as counterpoints:

Peripheral storytelling must create contrast with genre.

Whereas the show The Mandalorian has some innovative touches, it is a spacefaring adventure much like the first three trilogies and other spin-offs, each of which expands the world of Star Wars without subverting audience expectations.

Lucasfilm does however have a history of unfinished and abandoned works that play with genre in a way that feels closer to peripheral storytelling. Most notable is 1313, an M-rated sandbox which sounded more like Cyberpunk 2077 for its dark approach to the source material.Sadly this game was dissolved when Disney yanked the plug on it, and now any adults-only Star Wars games seem indefinitely postponed.

Concierge, on the other hand, goes against the grain of the franchises’ trademarks genre—RPG-like adventures by aspirational protagonists punctuated by battles—and made a story that could be considered the polar opposite.

Peripheral storytelling must create contrast with scope.

When the Harry Potter movies made a combined $7.7 billion, it seemed another saga was inevitable. Warner Brothers contrived a tangle of backstory and plot points based primarily on a fictional Hogwarts book and tried to imitate the epic scope of the original eight films.

The results were mixed and many fans tuned out by the 2022 release of the final installment.

At the same time, Harry Potter fan fiction—much of which focuses on smaller moments in the world of the series—is more popular than ever, which is likely representative of true audience sentiment.Today there are 26 seasons of Pokémon’s flagship anime series, 23 feature-length films (few of which are released in the United States) and over 150 games. Most of these stories follow Ash, Misty, Brock and their Pokémon and the sweeping scope of their decades-long journey is epic.

Concierge is tiny in comparison.

The series is only four episodes long with each installment varying between 15 and 20 minutes in length. It feels very intentional on the part of The Pokémon Company to have Concierge work with such a small canvas.

Peripheral storytelling doesn’t “hint” or tie-in to a franchise’s canon.

Born from the Shrek movies, the Puss in Boots franchise experiments on many interesting levels—its Netflix series aesthetically departs from its predecessors by drawing inspiration from comics and hand-painted animation and The Last Wish makes bold storytelling decisions, bringing complex questions about mortality into the story.But it’s still a mainline entry into the series canon which aligns audience expectations with the other films, inviting comparison.

Peripheral storytelling calls for a lighter touch. The question of what is and isn’t canon is central to defining what stories can be peripheral and The Pokémon Company has laid the groundwork for many years.Their anime follows one canon and the games follow another; stray adaptations like Concierge, Detective Pikachu, and the upcoming PokeTsune are made possible because the world of Pokémon feels realer in the imaginations of fans because of that careful separation.

When a story’s “world” is thoughtfully divorced from its most recognizable characters, assets, and events, a true storyworld is born.

WORKING WITH IMAGINATION

Matthew Ball says the three-step formula for creating a successful media franchise in the 21st century is to “tell stories, create love for those stories, and monetize that love.”

Many brands don’t have a problem with steps 1 and 3. And by only nailing those, many franchises are successful.

It’s step 2, though, creating love for those stories, that’s the kicker.

Love takes time and when you’re dealing with longer timeframes, your fans will be growing and changing. That means you must contend not only with your fans, but your fans' memories of what they once loved about your stories. And brands that nail that are the best in the world.

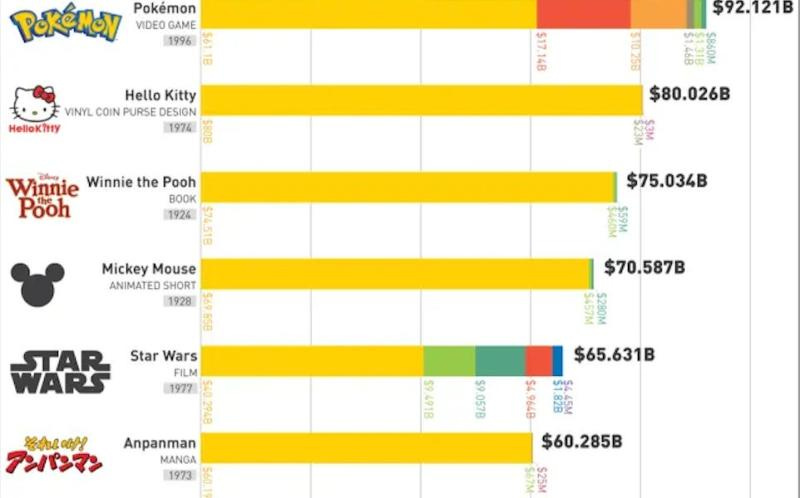

At the time of writing, Pokémon is the most valuable media franchise. It is worth more than Star Wars, Marvel, Harry Potter, or even any news organization. And I believe it is because they nail step two so beautifully.

Peripheral storytelling isn’t the whole story, but it’s one ingredient in their success. They put the ambient temperature of the franchise on full display, allowing fans of all ages to engage with the franchise however they want.

On a corporate level this requires enormous courage and artistry, which is why Pokémon Concierge is such a rare gem.

Thanks for reading! Please consider subscribing.

![Star Wars: 1313 - E3 Demo Full Gameplay [HD] Star Wars: 1313 - E3 Demo Full Gameplay [HD]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!wEkG!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb9490928-b885-4a77-9e3a-536d6504b471_1280x720.jpeg)